If, however, the man's breakdown did not follow a shell explosion, it was not thought to be 'due to the enemy', and he was to labelled 'Shell-shock' or 'S' (for sickness) and was not entitled to a wound stripe or a pension. Shell-shock and shell concussion cases should have the letter 'W' prefixed to the report of the casualty, if it was due to the enemy in that case the patient would be entitled to rank as 'wounded' and to wear on his arm a ' wound stripe'. In 1915 the British Army in France was instructed that: In spite of this evidence, the British Army continued to try to differentiate those whose symptoms followed explosive exposure from others. Since the symptoms appeared in men who had no proximity to an exploding shell, the physical explanation was clearly unsatisfactory. Evidence for this point of view was provided by the fact that an increasing proportion of men suffering shell shock symptoms had not been exposed to artillery fire. Īt the same time an alternative view developed describing shell shock as an emotional, rather than a physical, injury. Another explanation was that shell shock resulted from poisoning by the carbon monoxide formed by explosions. Some physicians held the view that it was a result of hidden physical damage to the brain, with the shock waves from bursting shells creating a cerebral lesion that caused the symptoms and could potentially prove fatal. The number of shell shock cases grew during 19 but it remained poorly understood medically and psychologically. Some 60–80% of shell shock cases displayed acute neurasthenia, while 10% displayed what would now be termed symptoms of conversion disorder, including mutism and fugue. The term was first published in 1915 in an article in The Lancet by Charles Myers. The term "shell shock" came into use to reflect an assumed link between the symptoms and the effects of explosions from artillery shells. By December 1914 as many as 10% of British officers and 4% of enlisted men were suffering from "nervous and mental shock". While these symptoms resembled those that would be expected after a physical wound to the brain, many of those reporting sick showed no signs of head wounds. In World War II and thereafter, diagnosis of "shell shock" was replaced by that of combat stress reaction, a similar but not identical response to the trauma of warfare and bombardment.ĭuring the early stages of World War I in 1914, soldiers from the British Expeditionary Force began to report medical symptoms after combat, including tinnitus, amnesia, headaches, dizziness, tremors, and hypersensitivity to noise.

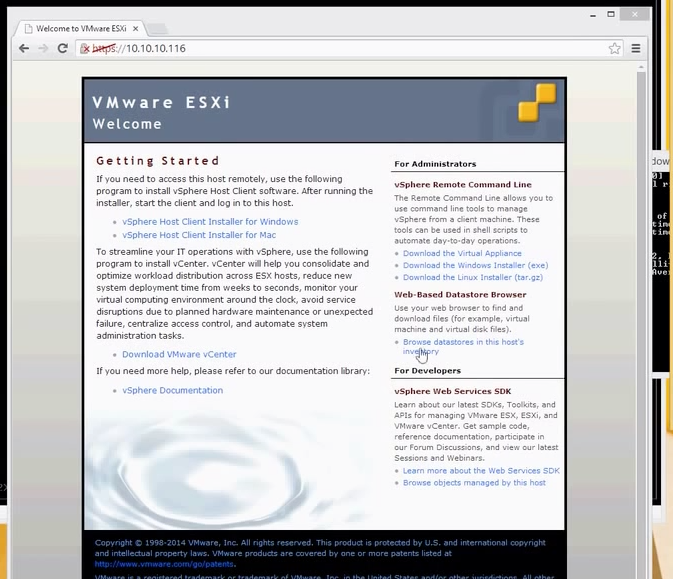

The term shell shock is still used by the United States’ Department of Veterans Affairs to describe certain parts of PTSD, but mostly it has entered into memory, and it is often identified as the signature injury of the War. Cases of "shell shock" could be interpreted as either a physical or psychological injury, or simply as a lack of moral fibre. ĭuring the War, the concept of shell shock was ill-defined. It is a reaction to the intensity of the bombardment and fighting that produced a helplessness appearing variously as panic and being scared, flight, or an inability to reason, sleep, walk or talk. Shell shock is a term coined in World War I by British psychologist Charles Samuel Myers to describe the type of post traumatic stress disorder many soldiers were afflicted with during the war (before PTSD was termed). Window.addEventListener('keydown', function(e) else if (node.tagName = 'SCRIPT' & (" wind, soldier's heart, battle fatigue, operational exhaustion Ī soldier displaying the characteristic thousand-yard stare associated with shell shock.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)